Aimée Crocker & Hori Chiyo: The History of Tattoos in the West

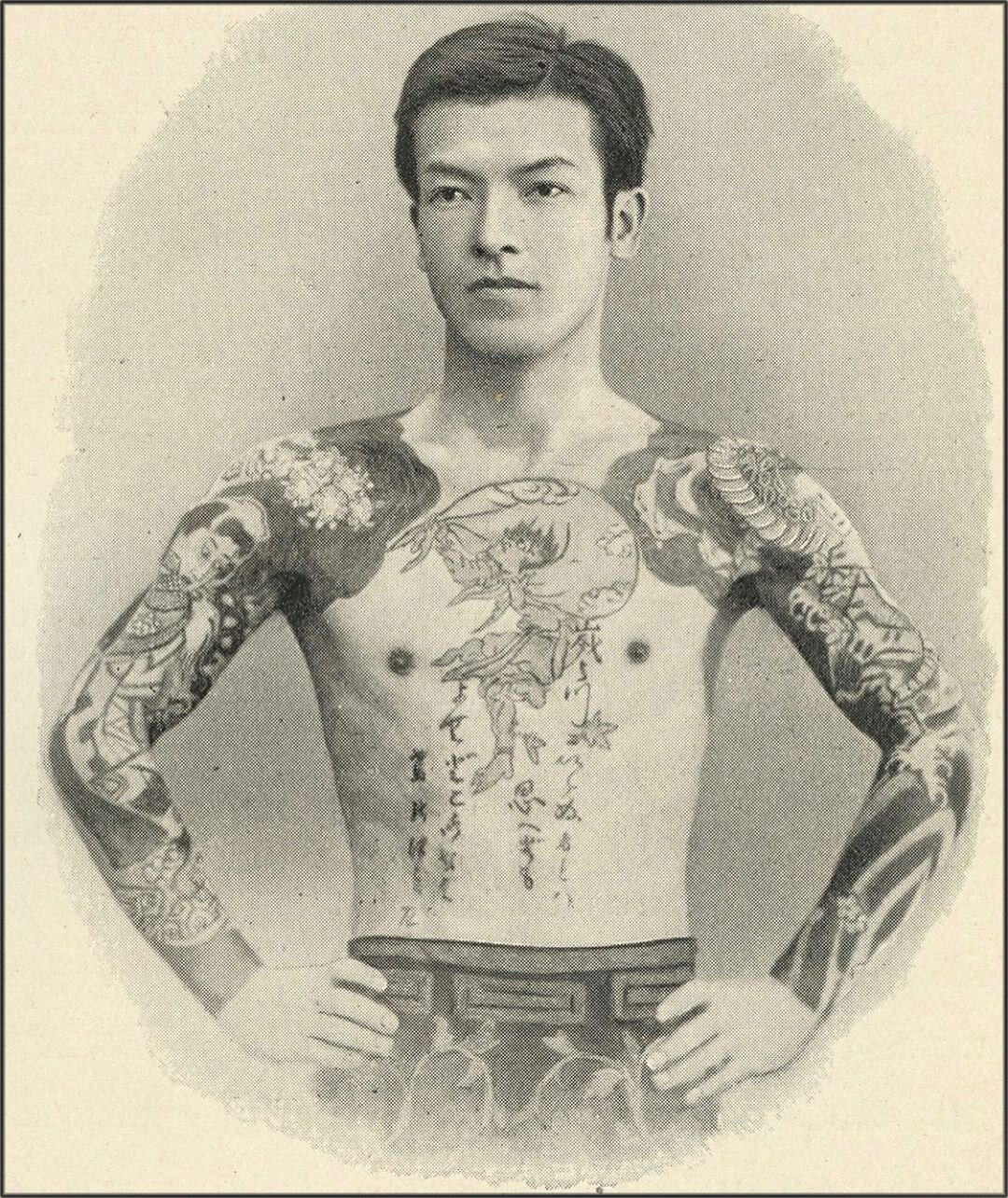

Illustration by Harry Fenn from a photo of Hori-Chiyo, “In the Track of the Sun: Readings from the Diary of a Globe Trotter” by Frederick Diodati Thompson (London: William Heinemann, 1893), p 45.

This essay was written by writer and historian Kevin Taylor and edited by me. It appeared on crockerart.org on September 18, 2020. Click here to see the original article.

Aimée Crocker — heiress, princess, mystic, and author — was a tattooed woman. She might have gotten her first tattoo during one of her four journeys to Hawai‘i or one of her two extended tours of Japan and Singapore. Or maybe it was during an eventful trip around the world in 1895. News that the Aimée Crocker had become a “tattooed woman” became public knowledge around the turn of the 20th century, electrifying her admirers and horrifying high society.

Aimée remarked, “The free life of wandering had gotten into my blood and the result was that my assimilation into Western living was a fairly complicated process . . . They made me out to be a rather scandalous sort of person, but I think the fun was worth it and that the joke was on them.”

Aimée devotes a few pages of her memoirs to legendary Japanese tattoo artist Hori Chiyo who may have given her at least one tattoo, as he did with so many other adventurous Western aristocrats. Chiyo was known for his use of bright colors, complex patterns, and expressive designs, as well as his innovative, anatomically-designed Kanto style, whereby a design was so arranged that it represented one thing when the muscles and skin were relaxed, and a totally different idea when they were flexed and tightened. Aimée claimed that Chiyo was an artist of the first order, “a rather remarkable fellow in every way. To look at him, you would believe that he had stepped out of a gaudy melodrama during the intermission and had just neglected to remove his make-up and change his costume.”

After the Japanese government cracked down on tattooing, artists like Chiyo were forbidden from tattooing Japanese citizens. However, a loophole allowed them to tattoo Western travelers visiting the country, who were becoming increasingly enamored by the opulent exoticism and exciting new aesthetics of “the Orient.” His international repute instigated a worldwide wave of appreciation of tattoos. Hori Chiyo himself would later etch dragon designs on the arms of the Duke of Clarence and the Duke of York (later King George V), the Duchess of Edinburgh, Queen Olga of Greece, and Czar Nicholas II of Russia.

A characteristic mark among instinctive and habitual criminals

Tattoo parlor in Japan, from “Illustrated London News” Dec 2, 1892, p12.

Tattoos appeared frequently on the bodies of the so-called “uncivilized” people that American and British imperialists and swashbucklers encountered during their explorations. Until Captain Cook’s first voyage through Polynesia in 1768, tattooing was an art unknown to the western world.

The word tattoo is one of only a few words used internationally with a Polynesian origin, coming from the word tatau in Tahiti, Tonga, and Samoa. In Hawai‘i the word became kakau. It was seamen who began exporting the practice, becoming walking galleries with great flags on their chests, scandalous mermaids on their biceps, and anchors on their shoulders. Tattoos became a sign that the wearer had made long voyages to exotic shores of palm-fringed islands. Soon other rugged and adventurous men adopted the fad — soldiers, cowboys, miners, loggers, hoboes, and circus performers.

Italian criminologist Cesare Lombroso’s famous 1876 study, L’Uomo Delinquente, is credited with the founding scholarship for the science of criminology. His study attested that criminality — which he believed was inherited — could be identified by the presence of a tattoo. Lombroso proved to his own satisfaction that tattooing was a characteristic mark among instinctive and habitual criminals and especially among those guilty of assault and murder. “While murderers and those of brutish inclination indulge in it,” he said, “forgers and swindlers, whose intelligence is on a higher plane, do not practice it.” In The Female Offender, Lombroso claimed that tattooing occurred at a higher number among prostitutes than other female criminals.

Hori Chiyo design, colorized by Baldo

In the United States, tattoos were relatively common among female circus performers. America's first professional "tattooed lady" was Nora Hildebrandt, whose German-born father Martin Hildebrandt owned the first tattoo parlor in America. In her fictional biography, Nora claimed to have been kidnapped by Sitting Bull himself, who, along with his tribe, forced father to tattoo daughter. Every day for a year — so the story goes — she was tied to a tree until she was tattooed from head to toe. Such fictitious stories of abductions became part of the act of other tattooed women in sideshow attractions.

In Europe, the list of crown heads who had their bodies illustrated in the 1880s and 1890s is extensive. These noblemen and noblewomen’s tattoos were often very Asian and featured elaborate designs. In time, the tattoo became a commodified product of colonialism.

Princess Chimay, formerly Clara Ward of Detroit, is perhaps one of the more notable examples of tattooed European nobility. The American expat had a whole art gallery of designs tattooed all over her body. She famously hired Londoner Tom Riley to tattoo a snake and a butterfly on her upper arm, as well as a picture of the man she dumped her Belgian prince for — a Hungarian gypsy fiddler named Rigo Janczy. The Princess later had an American eagle tattooed between her shoulder blades. After she dumped Rigo, Riley was hired again to cover the illustration of his face with a poppy. Techniques were vastly different during the fin de siècle. Riley would sometimes use a little cocaine to deaden any slight pain.

Hori Chiyo design, colorized by Baldo

Lady Randolph Churchill, Winston Churchill’s mother, is said to have had a tattoo of a snake eating its own tail, a symbol of eternity called an ouroboros, etched around her wrist which she covered with a diamond bracelet at formal occasions.

In 1896, society don Ward McAllister, of Mrs. Astor’s The Four Hundred fame, lamented, “It is certainly the most vulgar and barbarous habit the eccentric mind of fashion ever invented. It may do for an illiterate seaman, but hardly for an aristocrat. Society men in England were the victims of circumstances when the Prince of Wales had his body tattooed. Like a flock of sheep driven by their master, they had to follow suit.”

"The Tattooed Countess"

Appearing on the bodies of the foreigner, the law-breaker, the lower classes, and the innocent victims — the tattoo carried uncivilized, criminal, brutish, and masculine connotations. While there were reports of fashionable society women being tattooed, they certainly kept them well covered up while in public. Not Aimée Crocker.

In the spring of 1899, Aimée sent one of her Japanese servants to the Chatham Square studio of renowned Bowery tattoo artist “Professor” Samuel O’Reilly with a request to provide one of his Japanese assistants to her residence. O’Reilly was the first to use the electric process of tattooing, speeding up the work enormously, and coining him a fortune. He called his tattoos “tattaugraphs.” Hori Chiyo’s world-touring apprentice-turned-master Yoshisuke Hori Toyo — a visiting partner of the illustrious Bowery tattooer — was the skillful designer who showed up at her apartments. Hori Toyo was the master “tattaugraphist” who tattooed Lady Churchill, as well as the Duke of Marlborough, King Oscar II of Sweden, and Prince Waldemar of Denmark. He claimed his secret Japanese ink could retain its brilliancy for twenty years.

Design by Yoshisuke Hori Toyo from “Tattooing is a New Social Craze,” “Chicago Tribune”. January 8, 1899 p39.

Hori Toyo on two separate occasions tattooed on Mrs. Gillig’s arms a demon’s head, a Japanese beetle, and two snakes, one twisted to make the initials “A.G.,” the other, the initials “J.G.” About the same time, Jackson Gouraud also sent for O’Reilly’s Japanese artist and had the same initials reproduced on his arm. Aimée would later proudly exhibit her expression of sentiment at all the functions of New York and London, Paris and Newport, Nice and Cairo. The inking of her arm with her new beau’s initials came before the inking of her divorce decree from Harry Gillig, which finally happened in December of 1900. Aimée and the young Piccadillian eloped less than six months after the 1901 divorce from Harry, in England. They took apartments at the Hotel Scribe in Paris for their honeymoon. Unlike the traditional tebori (hand-done tattooing) of his mentor, Hori Toyo used an electric tattoo machine — of which his colleague O’Reilly obtained the first patent in 1891.

In 1901, Aimée was officially outed as a tattooed woman in a full-page color feature, which included a sworn notarized statement by Samuel O’Reilly himself. Aimée embraced this new jolt to her celebrity. Unlike other socialites, she was even photographed with her tattoos proudly on display.

Yoshisuke Hori Toyo, from “Tattooing is a New Social Craze,” “Chicago Tribune”. January 8, 1899 p39.

By the 1920s, mythical origin stories of Aimée’s tattoos appeared. The Daily News reported that she received one of her tattoos by a lithe native Indian boy, who became a soul mate. One day under the trees while living, “in the open, with the untamed of the animal kingdom,” the young man, “decorated the beautiful textures of her perfect skin with the indelible tattoo of his people.”

In 1925, it was reported that a then 60-year-old Aimée Crocker astonished New York society when she returned from Europe on the Cunarder Berengaria, “with two elegant specimens of chromatic needlework on her person. On one of her legs had been delicately and colorfully etched a snake, a symbol of health. On her back a butterfly, a symbol of the soul, poised as if for flight, had been stenciled by the deft puncture of the tattooer.” On her arm was a new husband — her fifth — 26-year-old Prince Mstislav Alexandrovich Galitzine, Count Ostermann, of Russia. The press dubbed her “the Tattooed Countess.”

Aimée Crocker’s tattoos were an assault against the suffocating gender roles of Victorian America. They transcended class boundaries. They convoluted racial and gender identities. They crossed borders. They transformed her into Gilded Age America’s most alluring spectacle. Crocker’s tattoos were signage indicating new unpaved roads still under construction were just ahead.